Sisters and brothers, grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

For Christ did not send me to baptize but to proclaim the gospel, and not with eloquent wisdom, so that the cross of Christ might not be emptied of its power. For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.

Last night I got a message that a member of our community was in the ER at Presbyterian hospital. So I put on my clerical shirt and a jacket and drove down there.

As I came into the building a family was leaving. Someone waved and said “Hola, Padre!”

“Hola!” I said in return. I didn’t know what else to say. The thing about being out and about in a clerical shirt is that you stop being yourself and you start being the church for whoever sees you. And whatever they feel about the church and the faith—whatever experiences they’ve had—will be projected onto you.

I do not enjoy this. I want to have a one-page summary of Lutheran Christianity and my own short biography to hand to people just to clear up any confusion. I want to say “I have a wife and children and also I believe women can do this and I have no objection to your brother’s same-sex marriage and…” so on. But that’s not the point, because I’m not the point, and it doesn’t matter how particular and special I think I am. When I’m at a hospital in uniform, I simply represent something bigger than me. I represent the ministry of the church coming to someone who is sick.

I went in to see our dear sister in the ER. I did not have a good feeling about the situation so I did the ministry of the church for the dying. Just in case. I want you to know, if and when we come to this moment, that the commendation of the dying is a non-binding ritual. You should feel free to make a miraculous recovery! But we work from a precautionary principle in this business, so it’s better to do the rite and not need it than need it and not do it. “By your holy incarnation, deliver your servant. By your cross and passion, deliver your servant.” It’s just words. And I make the sign of the cross on the forehead with oil. It’s a strange moment. I am just a person in a uniform, reciting a script, in the presence of a person who may not even be conscious.

I chatted with the family members who were there and then left out the front entrance. Before yesterday, I had only been there during the day. I looked up and saw the hospital rooms lit up. Suddenly I imagined the many souls in that building—a Galileean fishing village worth of people—waiting for something to happen tomorrow. Some of whom would not live to see tomorrow. Something prompted me to stop and pray for all the people in that giant complex of buildings. God, please protect and heal them. I imagined the angels brooding over the building through the hours of the night. Then I drove home to my family.

The other day I read an essay by a writer whom, I will admit, I don’t usually enjoy but who caught my interest by writing about his own terminal cancer diagnosis. He is a New York art critic who came from a Lutheran family in Minnesota. Now he’s 77 with a few months to live. He wrote that atheism takes a lot of effort. After an adolescent embrace of atheism, he lost the energy for it and gave it up, especially after he got sober. Still, he wrote, “I regret my lack of the church and its gift of community. My ego is too fat to squeeze through the door.”

That’s something a lot of people could say if they are honest with themselves. I’m too clever, too wicked, too busy, too skeptical, too independent-minded, too particular in my tastes. I’m not needy, I’m not weak, I’m not susceptible to guilt or shame. I can get by without all of it.

And maybe that’s true! Maybe people really don’t need a forty-year-old suburban dad in a uniform to show up and recite a script when you may only have a few hours or days to live. To stand outside the hospital and pray for you in case you don’t have anyone else to do it. “Deliver your servant.” Part of me hopes it’s true, that no one needs that, because it’s certain that few people get it.

Paul’s readers in Corinth were steeped in a culture that prized wisdom and knowledge. Teachers and preachers in their world appealed to wisdom and knowledge, or offered wisdom and knowledge. “Eloquent wisdom,” Paul calls it. In other versions it’s “plausible wisdom.” Paul is saying, in effect, “I did not come flattering your ego. I did not come trying to make you feel smart. Because if I’d done that, I would have made the cross of Christ null and void.” The message of the cross is foolishness to this dying world, but to us who are being saved, it is the power of God.

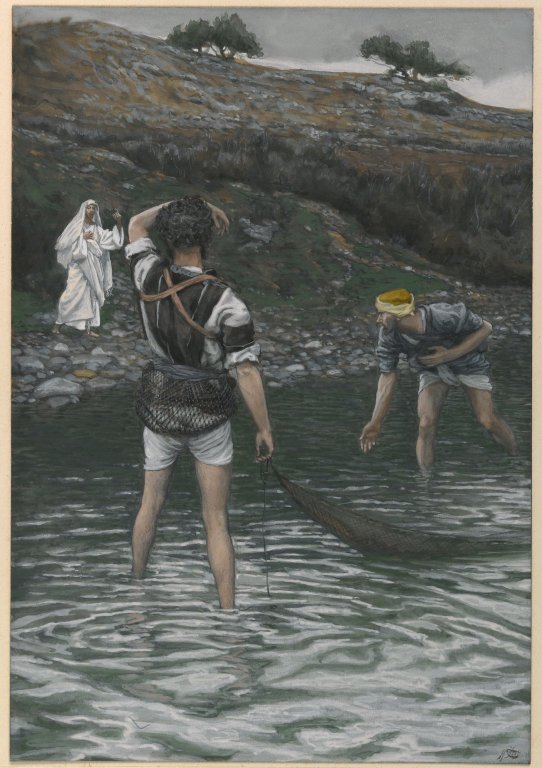

This is real. I know it’s real because I know how foolish I feel—how foolish I am—when I show up in my uniform to say my words and pour out my little vial of oil. I can just barely cram my ego into this collar sometimes. But that just means that all of the chips are down on Christ and his cross and resurrection, and I have nothing of my own to add. It goes all the way back, decades before anyone in Corinth heard of Jesus and before Paul himself had. It goes back to those first disciples that Jesus calls from the seaside. The whole neighborhood saw him and heard him. He was not well known, not a native. He had no miracles to vouch for his message. Indeed he was just saying what John the Baptist was already known for saying: Repent! Change your mind, because the kingdom of heaven is at hand.

We don’t know how many people said no or shook their head or asked for some time to think about it before Jesus got to Simon and Andrew. How many people were too clever, too wicked, too busy, too skeptical, too independent-minded to follow. How many people needed something more plausible, more eloquent than “follow me and you will fish for people.” Let me think about that, Rabbi, and I’ll get back to you. Then the hour or the day passes, and their neighbor Simon is gone. Where did he go? What did he find? Should I have gone too?

We only hear about the ones who said yes. We hear about Simon and Andrew, James and John. We don’t know what moved them in that moment—what they heard or saw that others couldn’t see; what motives they had that turned out to be wise or foolish. We only know that Jesus came down to the shore, to their work, to the midst of their journey from cradle to grave. He extended his hand and they took it. And the Body of Christ does not let go, even in the hour of our death. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed