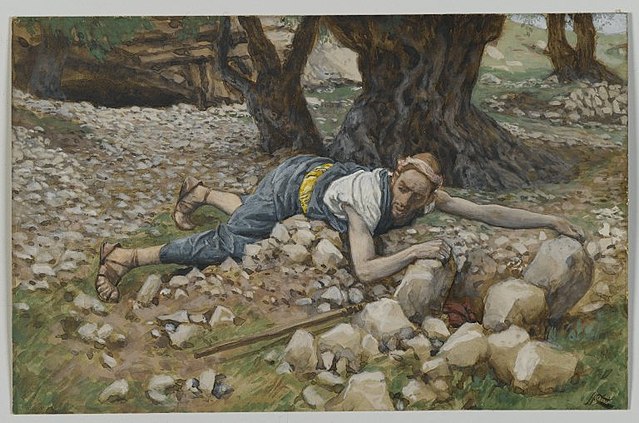

James Tissot, "The Hidden Treasure," c. 1890, The Brooklyn Museum

James Tissot, "The Hidden Treasure," c. 1890, The Brooklyn Museum First, to state the obvious: there is nothing good to say about a list in which "wife" is included among possessions alongside oxen and donkeys. And while there were meaningful differences between slavery as practiced in the the ancient world and as it was practiced in the Americas starting in the 17th century, it is lamentable that slaves were likewise listed alongside livestock as possessions not to be coveted.

Second, and rather less obvious: how exactly are we to refrain from not stealing our neighbor's possessions, or slandering our neighbor to get them, or harming our neighbor to take them, but from wanting to have what is theirs? What kind of religion polices not just your actions but your desires like his?

Paul the Apostle, writing to the church in Rome, gives us an answer:

Yet, if it had not been for the law, I would not have known sin. I would not have known what it is to covet if the law had not said, ‘You shall not covet.’ But sin, seizing an opportunity in the commandment, produced in me all kinds of covetousness.

Coveting is a very subtle sin. It's not coveting to say "I wish I had a nice house like my brother's," though that can be spiritually corrosive as well. It's coveting when we say to ourselves, "my brother's house should really be mine." Covetousness happens at a paradoxical intersection of resentment and admiration, hostility and envy. It can be worse than straightforward greed or acquisitiveness, because it involves telling a story about both ourselves and our neighbor. Not just "I want this" but "I deserve this;" not just "hers is nice" but "hers belongs rightly to me."

One of the unexpected ways this plays out in our world is in the controversial topic of Native American sports mascots. On one hand, people insist that a team name like "Redskins" or a mascot like Cleveland's Chief Wahoo is demeaning and offensive. On the other hand, defenders of the teams insist that no one names their team after something or someone they hate. And in a sense both are correct: the names and mascots are demeaning and admiring at the same time. Even in the 19th century Americans started to express a kind of nostalgia for the peoples our nation had conquered and replaced. The indigenous peoples of the Americas were identified with a noble simplicity, an authentic connection to nature, and all kinds of virtues we "modern" people had lost touch with. If you remember movies like Dances with Wolves or Little Big Man you may see what I'm talking about.

It is a very strange thing on its face to envy the people one conquers and even destroys. But that's how covetousness works: I want what I think you have, but I don't want you to have it.

By contrast, the parables we hear in this week's Gospel passage are about acquiring the Kingdom of Heaven in a much different way. A man finds treasure hidden in a field--by someone, at some time, for who knows what purpose--and instead of pilfering it he sells everything he owns to buy the field. A merchant searches for fine pearls and finds one so great that he gives up everything else to get it. The message of these parables seems to be that there is no shortcut to God's kingdom. You can't scheme it away or talk yourself into deserving it. It requires everything of us, without resentment or hostility, without envy or admiration for any human being. But instead of eating away at our souls, it makes us rich beyond compare.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed