Last week Soren and I visited London on our way to a workshop in Cambridge. It was Soren's first trip abroad and only my second time in London, so we were ambitious about what we tried to see. One very unusual London sight that caught his fancy was the Jeremy Bentham Auto-Icon, which is housed at University College London.

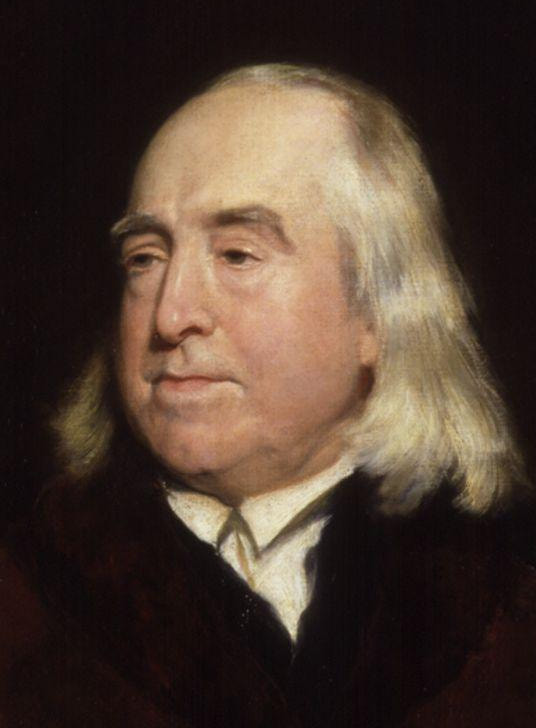

So in case the phrase "Jeremy Bentham Auto-Icon" is not super obvious, some background: Jeremy Bentham was a British philosopher and legal theorist who lived in the 18th and 19th centuries. Before he died, he made a provision that his body would be housed in a cabinet on display at University College London, an institution he helped found as part of his interest in higher education being more widely available to regular people. This Auto-Icon, or "self image," is on display today in the building that houses UCL's art museum.

As we walked up to the University I had the chance to tell Soren a little about this particular philosopher. He is considered the founder of the school we call "Utilitarianism," which finds the basis of law and morality in the good or bad outcomes (utility) of policies and individual choices. "The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation," as he put it in a formula that became famous.

I'm no expert on this history of philosophy but I find a lot to like in Bentham's utilitarianism. In some ways it is very close to the ethical worldview of early Christianity, where, for example, a person who had goods in excess of their needs was obligated to give that excess to people who did not have enough to meet their needs. "Your surplus belongs to the poor," the great preachers of the ancient church would tell their relatively well-healed urban hearers. That's to say: your third pair of shoes gives you less utility than they would give someone who had zero pairs of shoes. The same goods, distributed differently, can produce more or less happiness.

But, I explained to Soren, there are objections. For example, what if there were a being whose capacity for happiness was so great, whose ability to enjoy and make good use of everything so prodigious, that the only "utilitarian" arrangement would be to give that being everything? This thought experiment is called the Utility Monster, coined by a philosopher named Robert Nozick. It's an interesting idea--the most fun part of being a casual reader of philosophy is the thought experiments--but it never really made sense to me. The important thing after all is what economists call marginal utility, meaning the benefit you get from one more of something. So a utility monster would need to not just be able to get more enjoyment overall than everyone else put together, it would need to get more enjoyment out of its one-millionth pair of shoes than any shoeless person could get from their first pair. At that point you're talking about a god--an ever-hungry and mercurial ancient deity who can do nothing but take.

But, I went on (traveling with me is a lot of fun, as you have perhaps noticed), there's another, better thought experiment that argues against Utilitarianism. This is called the "Trolley Problem." In this scenario, there's an out-of-control trolley coming down the line. Ahead of it are three workers who will be killed if it doesn't change course. You have the power to pull a lever and send the trolley onto a siding where it will only kill one person stuck on the tracks. What do you do? The seemingly obvious answer is that you pull the switch. But, I asked Soren, what if the one person on the siding is the mother and sole support to five young children? But then what if the workers on the main line all have families depending on them? But then again, what if each of the three workers is actually Adolph Hitler? In thought experiments you can do anything, after all. The recent TV show The Good Place dedicated a whole episode to the Trolley Problem (making nerds like me swoon in the process).

The point, as I understand it, is that judging an action by its outcomes is a bad standard because the outcomes aren't knowable. Will my decision be more beneficial than it is harmful? Hard to say! It's a slippery and winding slope up to the summit of the greatest happiness for the greatest number, and none of us can see more than parts of the path.

After seeing the Auto-Icon, we needed to head toward a far away neighborhood to meet family, but we had just enough time to stop at another unusual London site: Postman's Park. In it is a monument devoted to "heroic self-sacrifice." The tiles commemorate people who died trying to save others, often strangers or unrelated neighbors. It's a deeply moving place.

Without meaning to, I realized, I'd stumbled into a park devoted to real-life Trolley Problems. It was a good place to go after seeing Jeremy Bentham who, good as his impulses were, did not leave any room in his system for heroic self-sacrifice. Lots of these people failed to rescue the people who were in danger. Those were the hardest ones to read. The sum total of human happiness would have been greater if most of these heroes had calculated that the odds of saving these other lives were too low for them to take the risk. Better for one of four to survive than for all to perish. These are people who answered the Trolley Problem by throwing themselves onto the tracks to save someone else, often to no avail. They broke the system.

After leaving the park our path wound past St. Paul's Cathedral. which brings me to the Gospel for this coming Sunday:

‘You have heard that it was said, “You shall not commit adultery.” But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to go into hell.

It is fair to say that these are not the most popular words Jesus ever spoke. They are hyperbolic (no one is saying you should literally cut off your hand), but even so they say something difficult: that it's better to suffer harm to oneself, or even to reject an important part of one's own life, than to do wrong to another. "My hand does more good than evil," I might tell myself. "The sum total of human happiness is greater if I keep it and do some sins than if I cut it off and bumble into heaven." And that may well be true! People have understandably found these words oppressive, or at least used in ways that made them feel wracked with guilt and unable to do normal things without feeling that they should be suffering more.

I don't think that's the meaning of these words. I don't think the Gospel points us toward hurting ourselves little by little so that we get better at avoiding sin. The Gospel is not an especially useful tool for avoiding sin in general, I don't think. At least there are better ones out there.

Instead, I think Jesus is telling us something about how important the moment is, how important our own lives and those of everyone around us are. Like the people remembered at Postman's Park. Some of them, maybe all of them, died with some unconfessed and unlamented sins on their heads. Some of them were perhaps not especially heroic or noble people before that moment. But when the time of testing came--we pray in the Lord's prayer that temptation not come, but eventually it does--they threw everything they had into the answer. We crave happiness but we love and admire those who do not count the cost in loving and serving others, starting with Jesus himself.

More links:

Here's what I preached the last time this text came up.

Eric Barreto, Workingpreacher.org: "But then Jesus raises the stakes here even more. Reconciliation is a prerequisite for coming before God at the altar. That is, what if broken relationships among neighbors, family, and friends are not just social obstacles among us but a barometer for our relationship to God too? What if the obverse of murder is not just avoiding killing but reparative reconciliation? That is, the command not to murder extends even beyond the taking of life. The rejection of the deterioration of someone’s character is essential in embodying the command not to murder.

Here's a short video on The Trolley Problem.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed